The anger because of billions lost through corruption and state capture comes at an enormous opportunity cost. The focus on the Zuma-Gupta-axis acts as blinkers that prevent a focus on the massive cost of adhering to failing economic policies and strategies – a cost far greater than the billions swindled away through corruption.

Three figures show clearly that the economic malaise is much deeper than the damage caused by corruption parasites and that the impact of poor policies started long before corruption landed under Government privilege at Waterkloof. Blaming the economic ills of South Africa on State Capture is a massive over-simplification.

Whilst getting rid of corruption should be supported, there remains a dogged adherence to a set of poor policies and strategies that undermine the prospects for investment and growth: bailing out a bankrupt SAA is one obvious example.

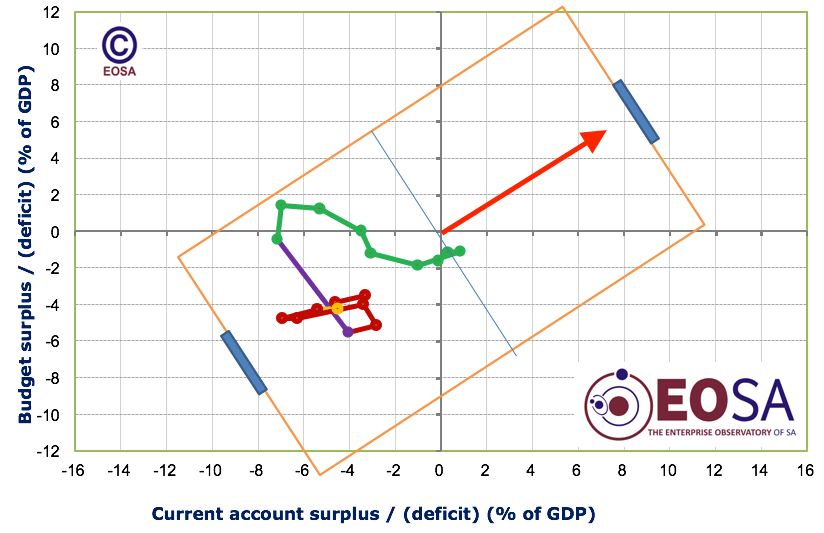

Figure 1 plots on a soccer field the performance of South Africa (with the budget surplus/deficit reflected on the vertical axis and the current account balance on the horizontal axis – both expressed as a % of GDP). Trying to score goals where the arrow points to is difficult when considering SA’s moves on the field.

The Mbeki-Manuel era (green) from 2000 to 2008 was the only time when SA could briefly record either a budget surplus or a surplus in the balance of payments. When GEAR and ASGISA were culled by the ANC and Mbeki recalled, the Motlanthe-Manuel (purple) move occurred. The Zuma-Gordhan eras (red) played directly in front of SA’s own goal area (the yellow indicates the Zuma-Nene combination).

Had Bafana-Bafana played as poorly as Government had managed the budget and the economic environment, they would have had more than the 16 coaches they had in that period.

However, Zuma received standing ovations and a vote of confidence from the overwhelming majority of ANC parliamentarians after scoring own goals (using public funds for personal purposes at Nkandla, then disregarding the Constitution by ignoring Madonsela’s recommendations, as well as the downgrading by Fitch and Standard & Poor).

Since GEAR was dumped, there has not been a single budget that was really growth oriented: all were aimed (when read together with BEE, sector charters and labour regulations) at increasing governmental intervention and control: own goals scored against economic freedom, growth and job creation.

One now hears the individual justifications from some senior politicians and officials (“I did not know…” and “We believed the attacks were orchestrated by a white monopoly capital conspiracy” and “It was only now that we heard the penny drop”). However, Figure 2 makes it clear that the writing was on the wall for all to see. In five global ranking indices SA consistently deteriorated from fairly good positions to positions of not only mediocrity, but notoriety.

Missing the dropping penny concerning one index is possible. Failing to hear the pennies dropping year after year on all these indices as if the purse was ripped open and not doing something about it, can only be ascribed to either utter ignorance or regarding the interests and unity of the ANC as more important than constitutional obligations, or a combination thereof. In that sense, the ANC caucus members from 2009 to now hold no different position than that of Zuma – no wonder he maintains that no-one had told him what he supposedly did wrong…

Figure 3 developed by economist Mike Schüssler on net Foreign Direct Investment (value of foreign fixed investments in South Africa minus the value of SA foreign fixed investments abroad) as a percentage of GDP, shows SA is a far bleaker investment prospect than during the heydays of apartheid.

FDI Investments during the 60s and 70s remained strong. There was only a net outflow when P W Botha in his disastrous Rubicon speech became more effective than the disinvestment campaign in instituting sanctions against South Africa. It was after that that Mobil, General Motors and others packed their bags and went. The release of Mandela, the commencement of negotiations and the 1994 elections did not rekindle net investment, mainly because since 1990 South African investors commenced investing on other shores: think Anglo American, SAB, Didata.

The elections of 1999 refuted the definition of African democracy meaning a once-off free election, it heralded a phase of increased FDI with a sharp dip in 2008 when the ANC in Polokwane rejected Mbeki as well as the GEAR policy framework. The depth of the international financial crisis also contributed. Net FDI peaked again with World Cup 2010 (though still far lower than in 1960 under Verwoerd). Thereafter it was over the cliff.

From 2014 when Cyril Ramaphosa became Deputy President and advocated in Davos and all other platforms that he addressed with Team SA that “SA is open for business”, investors used the open doors to get out. The exiting commenced long before the Guptas arrived at Waterkloof…

The data of Figures 1 and 2 shows why investors used the open door in a different direction that Ramaphosa had intended them to do.

These three figures jointly prove the ills of the economy (poor growth, low job creation, declining productivity, lack of investor confidence, policy uncertainty) precede the phase of State Capture. Anti-business policies and practices delivered exactly the outcomes that the average person would expect them to yield: poor growth, capital flight (both knowledge and wealth), entrenched unemployment.

These are not unintended consequences – they are the direct fruits of poor policy decisions and government practice.

The trends in the three figures have common roots: A deadly combination of economic ignorance and anti-business sentiment is at work. Are the facts that the cost of crime for business in South Africa is the 5th worst in the world, and that SA’s police force is one of the twenty worst on earth merely indicative of institutional incompetence and decay or are they manifestations of an outlook that view established businesses as the enemy of the masses?

Academics (Chris Rogerson and Etienne Nel) researching the dismal results of LED efforts mention a deep distrust at municipalities in the private sector and Moeletsi Mbeki talks of a marginalized business sector shackled with onerous taxation and even asset seizure.

The state was so easily captured because it was already so dismally weak and malfunctioning: from the police force to a parliament failing (through majority vote) in its constitutional obligations.

Rolling corruption back is the easier part. Achieving public efficiency and business-friendly conditions are far greater challenges and requires an understanding of and respect by the public sector for the world of enterprise and the market. That is where an unrelenting focus should be.

The commitment in Ramaphosa’s New Deal to State-owned enterprises as the pivot for economic well-being, as well as his embrace of property expropriation without compensation as government policy, are not signals that indicate a willingness to remove the blinkers and to make growth and economic freedom (competition, not prescription or monopolies) the key pillars to stop playing in front of one’s own goal area.

(This is the first of three reflections on the legacy of the Zuma-Motlanthe & the Zuma-Ramaphosa administrations on the economy and the world of enterprise.)

Excellent tying together of a number of loose ends. Pity that it has to amplify the bad news. Visionary and creative nonetheless!

LikeLiked by 1 person